Local curriculum design in technology: Tēnei au

Teaching inquiry

How can I get to know my students better?

Introduction

The year 9 Tēnei au project, was an integrated te reo Māori, English, and technology project. It involved a teacher inquiry about getting to know her students and learning inquiries focused on brief development and language skills.

The Tēnei au project allowed students to bring their backgrounds, and the knowledge and skills they have as a result, directly into their learning at school. Through their work on this project, students:

- experienced working to a clearly defined brief

- linked their experiences of creating a recorded introduction to the possibility of doing this for job applications in the future

- significantly improved their writing.

Teacher Clare Ravenscroft developed a deeper understanding of her students and of their unique identities as a result of the Tēnei au project. Relationships between whānau and the school benefitted from the input whānau had into the students' work and from the conversations between students, whānau, and teacher. This is an example of local curriculum design and building cultural capability.

Strategy

Beginnings

Tai Wānanga opened in 2012 on the Ruakura campus in Hamilton as a designated character school for up to 120 students. All students have individual learning plans, and the school emphasises project-based learning. The school had this vision:

“Tai Wānanga Ruakura will build its academic, sporting and cultural curriculum around discovery, technology, and innovation, taking advantage of its location and the inherent strengths in this role.”

Tai Wānanga Ruakura

Principal Toby Westrupp and his kaiako at Tai Wānanga Ruakura know the importance of validating student identity. Toby asked kaiako Clare Ravenscroft for her ideas on how to achieve this aim in a learning project. Clare, an English teacher who also has responsibilities for technology education, suggested devising a project that would link the two learning areas.

To support the development of her own skills, she became a participant in the “Teachers new to technology education” professional development initiative. At the first session, facilitator Lesley Pierce challenged her with this question:

“How can you get to know your students – particularly Māori and Pacific students – better?”

Lesley Pierce

This question is explored on New Zealand Curriculum Guides: Senior Secondary here.

Creating the project

On her return to school, Clare discussed the workshop with Toby, including the facilitator’s challenge and the understandings that she had gained about brief development. Clare was keen to come up with a project that would:

- incorporate the use of a brief

- validate student identity

- help her get to know her students better.

For Principal Toby Westrupp, “Tēnei au” was the ideal place to start. This tauparapara (chant) tells of Tane’s journey to the uppermost realm to gain the three kete of knowledge from Io (the Supreme Being). Tane’s journey is often used as a metaphor for a life well lived, in pursuit of tuauri, tuatea, and aronui (loosely interpreted as knowledge, education, and enlightenment).

“Tēnei au” provided inspiration for the students – prompting them to think about life as a journey and to think about where they had come from and where they wanted to go.

The idea was that each year 9 student would create a personal introduction, including their own mihi in which they introduced themselves and celebrated the things that were important to them. The personal introduction would have a visual, a written, and an oral component. It would be recorded digitally and it would be:

- made available to other kaiako

- made available to the wider school community

- used for research purposes

- kept as part of their school archives.

The brief

With the need established, Clare:

- taught the students the language of brief development

- gave the students the conceptual statement

- outlined the attributes required in the outcome.

“Tai Wānanga wants each year 9 student to introduce themselves in a way that reflects kaupapa Māori and is able to be recorded digitally. The presentation needs to include a spoken, a written, and a visual aspect. We have just five weeks to meet this brief.”

Clare Ravenscroft

A personal introduction: Brief

Conceptual statement

- to develop a Tēnei au presentation that describes who I am

Attributes

- Draws inspiration from “Tēnei au”

- Reflects kaupapa Māori

- Is recorded digitally

- Includes a spoken, written, and visual aspect

- Is completed in five weeks

Development

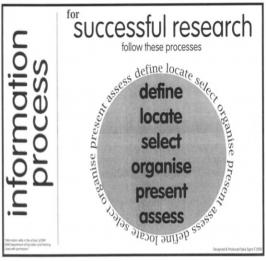

Clare outlined for her students an iterative process to be used when researching their whakapapa: define, locate, select, organise, present, and assess. Kaiako fluent in te reo Māori were available to assist students with their spoken and written language. Parents and grandparents became stakeholders because they were keen to ensure the students understood and accurately recorded their pepeha.

The students were required to consult at least three others – a kaiako and two classmates – when developing their personal introductions. The students were taught how to give effective feedback, and how to avoid being either too positive or too negative. A rubric outlining the required attributes of each of the three components helped focus feedback conversations.

The class decided that laptops would be the best way to record the spoken part of their personal introductions. When sound quality proved a problem, the students asked Clare if she could locate a microphone for them. As a consequence, the school bought a Bluetooth, wireless microphone. Clare thought that, next time, she would involve students in solving a problem of this kind.

The visual component of their personal introductions was to be of the students’ own choosing:

“For the visual component, the students were encouraged to add to the picture of themselves that they had provided in their speaking. When some students said they needed more direction, we talked about describing either a person who was important to them, or a place they really liked to be.”

Clare Ravenscroft

Halfway through the project, an interim assessment revealed that, while the students understood the purpose of the project, over half needed further coaching in sentence structure. At that point, most were focused on learning their pepeha and trying to find out further information on their maunga, awa, and marae. The students practised answering questions accurately and were challenged to show an improvement in their writing when the time came for a formal evaluation.

Outcomes

Student learning in technology

Apart from the whakapapa, it was very much up to the students to choose what content they included to fulfil the requirements of the brief.

Treo Tyzel Lord gave his mihi and spoke about his hobbies and his experience of Tai Wānanga in his video recording. His writing is a description of attending a tangi. (See the video and PDF below.) His visual piece was a PowerPoint presentation about himself.

Treo Tyzel Lord: The reunion (PDF, 111 KB)

For her spoken piece, Areta Jane Charlton gave her mihi and talked about her family and friends, coming to Tai Wānanga, and her aspirations. Her writing is a comparison of two places that are important for her and her whānau. (See the video and PDF below.) Her visual piece is a movie of her family and places they have traveled to.

Areta Jane Charlton - Mixed emotion (PDF, 118 KB)

Justice Apirana Hall gave his mihi in the video recording, and described the origins of his names and further information about his iwi. His writing is a description of taking part in a VEX Robotics competition. (See the video and PDF below.) His visual piece is a PowerPoint presentation about himself.

Justice Apirana Hall - Vex Robotics (PDF, 45 KB)

To assess the students’ learning, Clare developed a series of 20 questions. The first 13 were designed to assess their understanding against the achievement objective for brief development – several of these questions were derived directly from the level 1 and 2 indicators in the Indicators of Progression. The remaining seven questions asked the students to evaluate their outcomes for fitness of purpose against the brief.

Based on the feedback, all the students were at level 1 for brief development, and some were close to level 2. But given that the project was only five weeks in duration, Clare considered that any technology assessment data was necessarily formative.

Evaluation questions (PDF, 42 KB)

Improvements in students' writing

As an English teacher by training, Clare is very positive about the value of integrating aspects of the technology learning area with English:

“The technology learning area is very relevant to students. It provides a meaningful and engaging framework within which to develop their writing skills.”

Clare Ravenscroft

The students rose to the challenge of improving their writing, with 25 out of 29 meeting all the criteria. The following table, derived from a summative assessment of the students’ speaking and writing in English, shows the percentage of students at each level of the curriculum:

| English | Level 3 | Level 3–4 | Level 4 | Level 4–5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speaking | 11% | 14% | 50% | 25% |

| Writing | 25% | 25% | 40% | 10% |

Stronger relationships with students and whānau

The personal introductions increased Clare’s knowledge of her students; for example, she found that not all were Tainui – other affiliations included Tuhoe and Ngāti Porou.

“We learnt about their families, what they did outside of school, what was important to them, and why they had come to Tai Wānanga Ruakura.”

Clare Ravenscroft

As a result, she has been able to develop relationships with the students that are based on a deeper understanding of their circumstances and their unique identities. For example, when a student talks about a baby sister, Clare is able to respond with an understanding of the broader family context.

The project also meant that students engaged in conversations with their whānau about their whakapapa, and whānau could see that the school was actually doing as they wanted – using the culture as a basis for learning. Parents and grandparents were keen for the students to “do it properly”. Clare noticed that students who were fluent in te reo Māori were often able to present a more in-depth whakapapa, covering several lines of heritage.

General outcomes

Clare and Toby were excited with the outcomes. Clare says:

“We have become aware how much unstructured learning (unexpected learning outcomes) occurs when the students are working on a project like this.”

The school aims to develop project-based learning in a culturally responsive context – and this is a step in the right direction.”

Clare Ravenscroft

The students understood that, in the future, they may have to prepare a recorded introduction for a job application or interview. Some were really pleased to have the opportunity to learn more about where they came from, and to discover that their own whānau was such a valuable source of knowledge.

And all had experienced, perhaps for the first time, the benefits of working to a clearly defined brief.

What next?

Clare’s students are soon to begin a major new project, which is to develop an ethno-medicinal garden. This time she plans to build on their language skills while focusing on another component of the technology learning area: characteristics of technological outcomes.

Clare intends to get the year 9 students analysing technological outcomes that have impacted on their lives (nature of technology strand):

“If the students can understand more about the made world, then I think they will see why we study technology, and the relevance of this learning area.”

Clare Ravenscroft

Clare concludes:

“We are definitely learning together. The ethno-medicinal garden will provide a rich context for enhancing students’ understandings in brief development and technological modelling. The science teacher will also be involved in this project.

My goal in English is to provide further practice in the research process, to develop skills in visual literacy, and to teach effective log and report writing. Planning for practice (from the technology learning area) could provide an anchor for log writing. One of the issues I had with log writing last year was that the students did not know how to talk about what they were doing.

For the te reo Māori component, we initially want students to learn the Māori names for medicinal plants, and to explore whakataukī related to New Zealand native plants.

We are being encouraged to explore kaupapa Māori contexts and to teach through the context rather than teach the culture. Toby will launch the ethno-medicinal garden project with the students during Matariki."

Clare Ravenscroft