Costume inspired by a longhorn beetle

Introduction

Maia Holder-Monk, a year 13 student at Wellington High School, was one of the lucky students who designed and constructed a wearable art costume to be displayed in the Te Papa Store window display in Brandon Street during the World of Wearable Art festival.

Don’t let assessment be the driver - take an Assessment for Learning approach

Kylie Merrick, Maia’s technology teacher, follows the premise in her teaching practice that authentic and local contexts for learning about technology leads to assessment rather than the assessment being the driving for programmes. She sees Maia’s project as a clear example of this. The project:

- provided evidence for multiple assessment opportunities

- was a high stakes project that was complex enough to encourage the critical thinking required for a scholarship submission

- required extensive and on-going communication with a wide range of experts and stakeholders.

The brief from Te Papa

The students were initially provided with a range of photographs from the Te Papa collection, with a focus on texture. From these, they selected an inspiration image for their work.

The manager of the WOW windows encouraged the students to think about the requirements of an effective window display, discussing strategies such as bold colours and silhouettes.

Te Papa also provided the students with two sheets of a commercially printed PVC billboard banner. One of these sheets had to be incorporated in the backdrop and another was to be used in the outcome.

The challenge

The challenge for the students was to produce an outcome that:

- met the needs of the Te Papa store and their window displays

- worked well with the other work that would share the window space

- reflected a message that would suit the WOW festival

- fitted a static pose mannequin.

As well as all the above, the outcome had to fulfil the requirements of NCEA level 3 technology and the technology scholarship standard!

One of the expectations of level 8 in technology is that an outcome must be seen as fit for purpose in its broadest sense. Fitness for purpose in its broadest sense refers to the wearable art outcome, as well as the practices used to develop it. Judgements about fitness for purpose may include:

- considerations of the outcome’s technical and social acceptability

- sustainability of resources used

- ethical nature of testing practices

- cultural appropriateness of trialling procedures

- determination of life cycle, maintenance, and ultimate disposal

- health and safety.

Development

With her interest in armour, Maia selected the Longhorn beetle from the range of photographs provided by Te Papa.

She made connections between the beetle’s armour and the way that women warriors are depicted in modern media and video games through the over-sexualisation of their armour.

It’s one of the worst examples of patriarchal oppression in our society in that characters who are male are designed with practical strong and defensive armour – whereas female characters get stuck with a metal bra, tiny shorts, and thigh high metal boots. This complete destruction of the purpose of armour (to defend oneself) is something I would like to combat in my wearable art piece.

Maia Holder-Monk

Maia read and researched Dieter Rams’ 10 Principles of “Good Design” to provide a basis to critique her development work.

These principles also helped to guide the outcome development and ensure that it would be fit for purpose in its broadest sense. For example, the principle “good design is environmentally friendly” was seen in her use of recycled and preserved products such as the bottles she used for the antennae.

Making the costume

Te Papa allowed Maia to manipulate the original beetle image, scale it, and print it multiple times onto one length of the PVC. This was incorporated into shoulder pads, parts of the bodice, and the pants.

The pants

The pants proved to be a particularly challenging aspect of the outcome. The mannequin provided by Te Papa was in a fixed position so the pants needed to fit this pose.

Maia learnt pattern drafting skills and drafted a basic skirt block to fit the mannequin, adapted this to culottes, and then to a more fitted style. The progression of skirt to culottes to pants was due to the mannequin’s unusual pose. The progression also allowed for better fitting stages for around the waist, crutch, and leg.

The calico toile fabric, a woven fabric, had different properties to the unforgiving plastic vinyl and Maia found that when she made up the final pattern in the printed vinyl, the pants were too tight.

Maia solved the problem of the pants’ fit by adding an apron to the vinyl shell top (the upper garment), which then covered the top of the pants. Part of the philosophy of the garment was to make links to western women’s fight for equality. An apron was seen as a garment with connections to women’s traditional roles, and hence provided a link with the narrative of the outcome.

The outcome provided an extremely rich context for learning about materials – their properties and how to manipulate these.

For example, when sewing the vinyl, Maia used a teflon foot to sew the seams in order to address the material's “sticky” property and to ensure the fabric would glide under the foot easily. She also used a zigzag stitch to flatten the seams and tape rather than pins to prepare pieces for sewing because pins leave permanent perforations in vinyl, which could lead to tears.

The armour

The outcome included multiple pieces of armour.

Thighs

Inspired by Roman tab leather armour, Maia filled small resealable bags with shredded paper printed with a rectangle repeat print of the longhorn beetle shell. She layered these to create armour for the upper side leg.

The resealable bags were sewn to a panel and domed to the pants at the hips. The shredding of the paper added an element of camouflage to the armour, similar to the camouflage used by the longhorn beetle in its habitat.

Shoulders

The shoulder pod armour was created using a wire armature to form the light-weight shell. Once the shape was created, Maia draped calico over the wire and created a pattern that then could be used to cut accurate shaped pieces from the printed PVC banner vinyl.

The two shoulder pods were attached with cotton tape to make them flexible to put on and off the static mannequin. Chainmaille attached to the shoulder pods and linked them to the chest armour.

Chest

Maia created an additional tube of armour, similar to a breastplate, which encircled the entire upper chest. Under the makeup pads, a lightweight chicken wire armature was made to form a 3D bulbous and voluminous shape. This allowed for the quilted makeup pads to stretch over and be attached easily, and for the chainmaille to link and attach into.

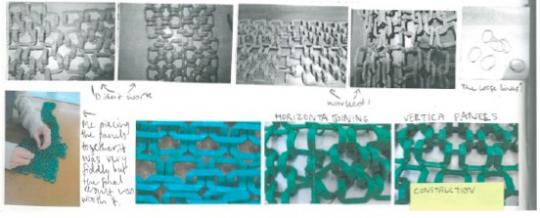

The chainmaille

Maia has always had a keen interest in the work and products of the Weta Workshop and had attended a workshop at Weta. She was particularly interested in chainmaille and had tried producing this in the past in a jewellery unit. The school had recently acquired a 3D printer and Maia saw this as an opportunity to explore and print her chainmaille using this new technology.

She approached the DGTM (digital media) teacher who managed the school 3D printers, chose a chainmaille that appealed, and then set up the printer to print this in the textiles room. The printing of these pieces was a lengthy job so Maia was able to set the machine up and print the material each day while she worked on other tasks. The chainmaille took 88 hours to print. Each piece was removed from the raft they were printed on and, following some experimentation, joined together with garden ties. The chainmaille was attached to the shoulder armour piece and sat up around the head and shoulders.

The 3D printing is seen as an additive manufacturing technique, which was more economical than subtractive manufacturing and minimised waste. This was another aspect of the outcome that addressed fitness for purpose in its broadest sense.

Maia looked into the practice of other WOW designers including Rodney Leong. She was taken with his idea of subcontracting the repetitive construction techniques and could see this would help to speed up construction.

I enlisted the help of some year 10 fashion students with repetitive tasks. I managed quality control and observed the time efficiency improvements that occurred when they filled the tiny resealable bags with the shredded paper, and broke the rafts off the chainmaille. I am confident in my choice to do this because it is a method used in the real fashion and technology world and acknowledges the realities of production.

Maia Holder-Monk

The antennae

Maia decided not to use the arms of the mannequin. The decision to remove them came from connections with avante-garde and the fact that the mannequin's arms were in poses that interfered with the look she was aiming for.

The forms of the antennae were brought in from the original stages of conceptual design and were reworked a number of times on paper. Maia carried out some modelling to work out scale sizes and what materials would be suitable.

The antennae were created from covering various sized recycled plastic bottles, including bleach, water bottles, and small soft drink bottles. The tips were made from glue sticks. The mechanical engineering teacher showed Maia how to use a circular drill to cut the bottles accurately to the required size, ensuring that they would link together by fitting inside each other. Maia glued these together, painted them silver, and covered them with a sheer black stocking – producing very realistic antennae. The antennae were attached to an ultra-cropped top that sat under the vinyl shell top.

A black swim cap covered the head of the mannequin down to the nose and a veil created out of chainmaille was attached to it.

Scholarship

Scholarship report: Maia Holder-Monk (PDF, 8 MB)

Maia was successful in scholarship in 2013.