Raising achievement in years 7–10 technology

Introduction

The technology department at St Peter's College has developed new programmes to:

- improve integration and coherence between the disciplines in technology

- support students to develop generic technological knowledge and skills

- support students in progressing through curriculum levels.

Background

St Peter's is an integrated Catholic co-educational school with students in years 7–13. Twelve per cent of the 418 students are Māori. The roll includes a number of students from Asia, plus exchange, scholarship, and fee-paying students.

The technology staff at St Peter's in Gore realised that developing technological understandings requires a co-ordinated approach – which made them rethink how they implement the curriculum.

Newly appointed HELA (Head of Essential Learning Area) Toni Tippett and her staff were keen to see whether a seamless programme would raise achievement and better prepare students for senior technology courses.

Toni, a trained design and technology teacher, says, “I was trained to think of technology as operating in a consistent and coherent way. This is the approach I have always taken in my practice.”

Whole-team planning

St Peter's offers technology across five disciplines: food, digital, textiles, product design, and DVC. The disciplines had been used to operating separately, with limited coordinated planning. This meant that there was no department-wide plan for new cohorts of students, with their varying levels of understanding and practical skills. Because plans focused on discipline skills, they did not cover generic technological practice or knowledge.

Toni says, “Teachers taught independently of each other, it was obvious we needed a coherent approach.”

Aware of the impact that whole-team planning can have on teacher understanding and student learning, Toni set up department meetings with the explicit aim of developing shared understandings of the learning area.

Developing new programmes

The department began developing new programmes. Teachers of the different disciplines engaged in serious discussion as they brainstormed how they would teach a particular component or meet particular indicators.

"Together we looked at how the indicators translate into the different disciplines so that teachers would feel confident teaching them – and would understand what they might look like in the other disciplines."

Toni Tippett

As a result, teachers made extensive use of the indicators and the accompanying teacher guidance. This was invaluable for reinforcing understandings and for relating understandings to prior learning. Teachers also learned to use the progression diagrams as a guide, not a rule.

Generic rotational building blocks

Inevitably, timetabling constraints meant that students encountered the five technology disciplines in different orders, so all planning had to take this into account:

"In schools, technology is generally taught in rotations, which can create disjointed experiences that have little continuity for students. To manage this issue, we planned a series of 'generic rotational building blocks'. Numbered 1–11, each block builds on the one before. Teachers concurrently build discipline knowledge and skills through project work. In this way, we know what students have already been taught – and what they need to learn before they move on. As a result, they encounter technology as a series of connected learning experiences."

Toni Tippett

Quality documentation

Once her staff had agreed on the structure of the new Technology programme, Toni used her skills in DVC to publish quality documentation for the department staff, students, and parents.

"We wanted our documentation and learning materials to have a department-wide identity. The similar look-and-feel of materials across the five disciplines reinforces for students that the different disciplines are all part of the one subject. It also helps students recognise that their knowledge and skills are transferable from one rotation/discipline to the next."

Toni Tippett

The common format of documents makes them easy for staff to use.

Outcomes

All year 7–9 students now follow a 3-year technology learning programme, with three rotations each year. Year 10 students can opt to study a half-year technology course in any of the five disciplines. All teachers use the generic rotational plans.

Rotation plan, year 7: Rotation 1 (PDF, 1 MB)

Year 7 product design student workbook (PDF, 7 MB)

Implementing the new programme

Toni says, “When we first implemented the new programme, we discovered that students did not understand why technology was part of the school curriculum, and they had little understanding of the made world.”

As a result, teachers now begin each rotation with a series of activities designed to engage students in big-picture technological thinking. These are based on an overarching theme for each year level:

- People and technology (year 7)

- Sustainability (year 8)

- Innovation (year 9)

- The past, present, and future (year 10).

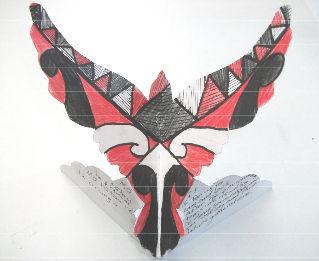

Each theme builds on a whakataukī and explores Māori perspectives. A key strategy is to use understandings developed in the nature of technology and technological knowledge strands to enhance practice and make learning relevant. For example, under Sustainability (year 8), one rotation looks at the difference between need and want, and the hidden ugliness behind products. The next explores how products can be valued differently across different cultures.

Year 8: A sustainable world (PDF, 432 KB)

"The teacher then identifies a sustainability-related issue, need, or opportunity as the basis for project work. For example, in product design we might explore how traditional skills can be passed from one generation to the next, while in textiles, students might look at how materials can be recycled or reused to make a product."

Toni Tippett

Student progress

When they arrive at St Peter's, most year 7 students are at level 2 of the curriculum, and they need to be at level 6 by year 11. Accordingly, teachers aim to have them working within level 3 in year 7, within level 4 in year 8, transitioning to level 5 in year 9, and at level 5 by the end of year 10.

"This is a challenge, particularly for technological practice, because the rotational timetable means that students may have only had two or three terms of specialist knowledge and skills in any one discipline over the four years that lead up to NCEA."

Toni Tippett

At the end of each year, members of the department review student achievement data and, based on what they find, modify the programme and activities.

Jointly developed exemplars (consisting of scanned and annotated student work) assist teachers to make robust judgments that are consistent across the department. Interdisciplinary moderation also helps ensure consistency.

"Staff bring student work to department meetings and we discuss where we think it sits and why, and what that student needs to do to progress – which builds a shared understanding of each level."

Toni Tippett

Exemplar: Outcome development and evaluation, early level 4 (PDF, 1 MB)

In addition to evaluating outcomes against the brief, they are rated for quality on a 4-star scale (1 star = low; 4 stars = high). Toni says we do this because, having spent about 50% of their technology time making their products, the students have a strong need to know how well their products have turned out.